Time for new traumatic brain injury (TBI) recovery expectations.

New Year. New concussion recovery expectations.

[Two Things. (1) The article contains some strong language. (2) Approaching mental/emotional growth can be triggering. Take it slow.]

It's finally the year 2021. 2020 is behind us, and sort of like a birthday - nothing feels much different. If you're unfamiliar with Mark Manson, he's the author of "The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck." Among the many books that I recommend to patients, this one is near the top of the list. It makes it in the top 10 because (1) it's hilarious, and (2) it provides an excellent framework for a resilient, at-ease mindset.

Not only hearing or reading but actually practicing "mindset techniques" or implementing "mindset tools" can be a massive breath of fresh air in concussion/PPCS recovery. Now, I know this is the last thing that anyone with persistent post-concussion symptoms (PPCS) wants to hear.

"You're telling me to be positive when I haven't been able to consistently handle a trip to the store without pounding headaches, dizziness, and fatigue for the last two years? Fuck off, guy. You take your positive magic fairy dust somewhere else."

Don't go yet, though. The point of this post is to start 2021 off with some validation (i.e., concussions/PPCS is real and sucks) and provide some powerful tools from the coaching world to get your year started on a solid trajectory.

Expectations & Validation

In the past few decades, concussion research has exploded, and it's been giving us a growing window into this invisible injury.

We are getting a better understanding of what is happening to your brain in an mTBI.

We have a growing knowledge of persistent post-concussion symptoms (PPCS).

The punchline of those three articles (and gobs of research) goes something like this:

Concussion (mTBI) is a functional and temporary brain injury. After a sufficient impact to the head or the body, your neurons (nerve cells) stretch and shear to cause a metabolic mess under the hood. The impact and metabolic chaos lead to autonomic disruption (blood flow irregularities) and an energy deficit. More than 90% of the time this happens without losing consciousness ("blackout").

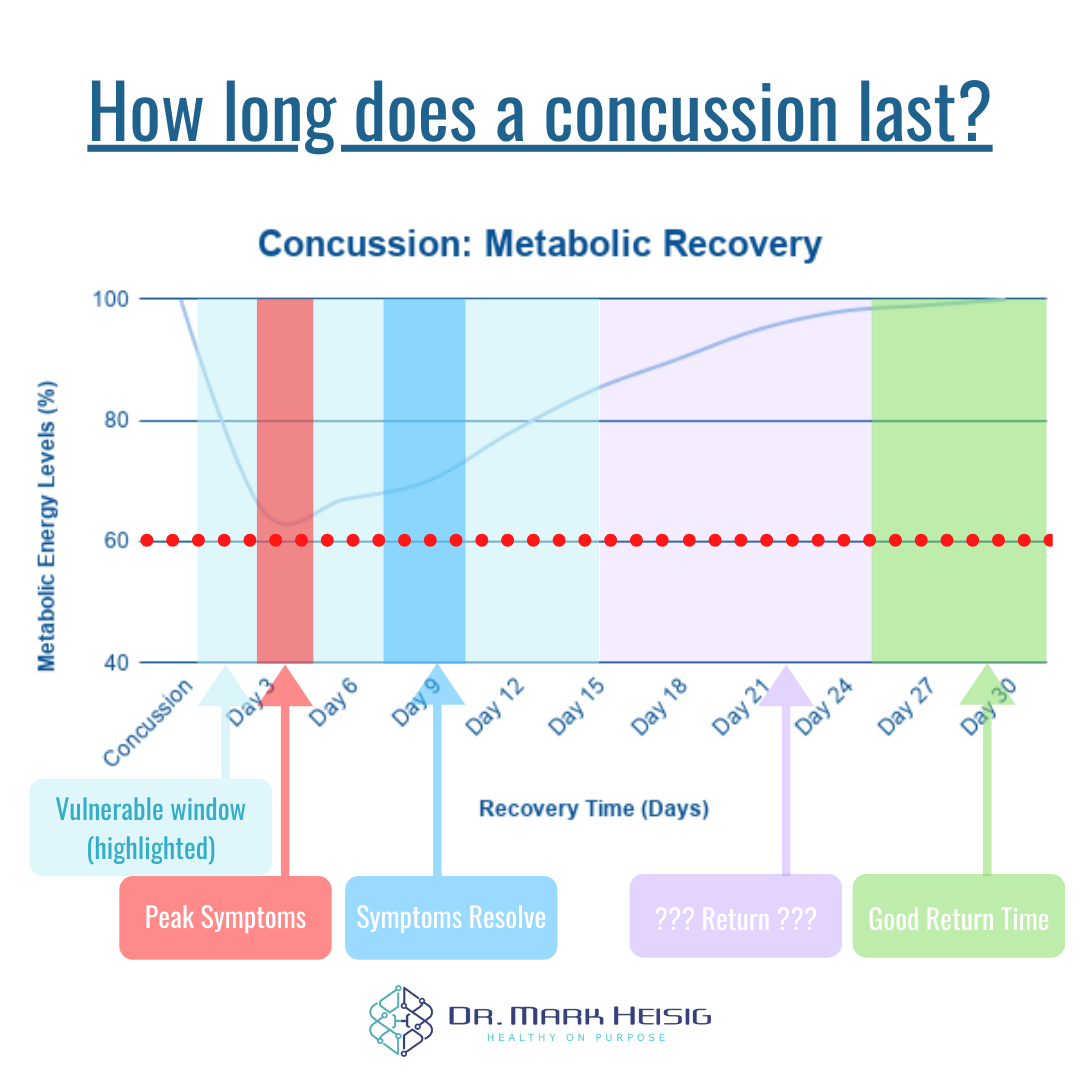

Concussion (mTBI) recovery takes 21-30 days, usually. In a typical acute concussion, symptoms will be at their worst 3-5 days after the injury. Shortly after, in around 7-10 days, symptoms should be mostly gone. However, brain metabolism (that energy deficit) is not healed for at least 21-30 days.

Persistent Post-Concussion Symptoms (PPCS) is considered when symptoms last longer than 14-30 days. According to the Berlin Concussion Consensus (2016), if symptoms last longer than 14 days in adults and longer than 30 days in childer, it is considered post-concussion syndrome (PCS; now called PPCS). We can safely assume that if the doctor says, "rest until your symptoms go away" (i.e., no treatment), that >30% of folks will go on to experience PPCS.

PPCS is not your "concussion," but it is another issue. We find that there are five "buckets" (or roadblocks) that lead to PPCS. There's an autonomic (blood flow), metabolic, visual/vestibular, cervical (spine), and psychological bucket. You can have just one or all five buckets involved in your recovery. Often, if you are an individual with years/lifelong PPCS, there is a mental/emotional trauma component, OR you sustained a TBI that was more severe than a concussion (e.g., moderate or severe TBI).

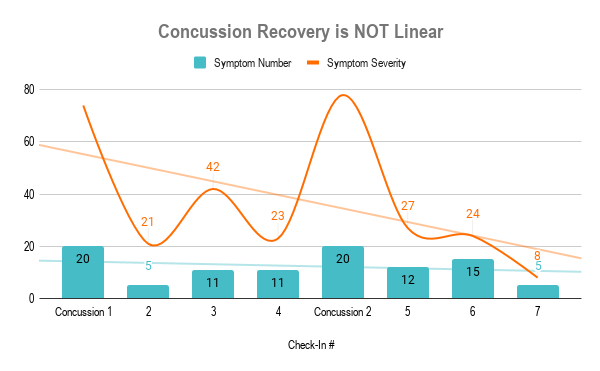

Recovery is not linear. Symptoms wax and wane. Some days you can exercise; other days, you're fatigued. Some days your head hurts; other days, your soaking in the sunshine without sunglasses. Concussion recovery is more like a roller coaster than it is a straight water slide.

Acute Concussion

As far as setting expectations goes, if you sustained a sizeable head/body impact and feel crummy for a bit over a week - that's normal. Ideally, you are aware of the symptoms and have a concussion specialist on board. Over the next month or two, your brain metabolism should restore to normal, and your life should resume as usual. With active and integrative therapies, we can solidly minimize your chances of PPCS. But remember, this process likely won't be linear.

Persistent Post-Concussion Symptoms

In the case that your doctor told you to rest, there's a >30% chance your symptoms didn't go away in the first 2-4 weeks. And it's likely due to an autonomic, metabolic, visual/vestibular, cervical, and psychological roadblock. This recovery certainly won't be linear. In any case, acute or persistent, a concussion specialist is someone you want on your team.

Making a case for a mindset practice.

"Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one's attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one's own way." - Viktor Frankl, Austrian Holocaust Survivor

I want to reiterate something here; that quote is from a holocaust survivor. Not a "restaurants are closed for indoor dining" survivor. Not an "I don't like wearing my face mask" survivor. That quote came from a Nazi torture camp survivor. (How's that for a guilt trip?)

The rest of this article is rooted in behavior change psychology strategies to help you shift your mindset for recovery and growth. Hopefully, we're going to help show you how you orient to your concussion and yourself - and if that serves you or not. For starters, @concussionperson123 on Instagram/Twitter, you are not your concussion; you're a fantastic and resilient human who's value and personality go beyond a cluster of symptoms - but we'll talk more about that below.

Sphere of Control: Outcomes vs. Behaviors

The sphere of control is your understanding of your power and your limitations. Your sphere of control will be an anchor point of sanity throughout acute and chronic recovery (and life, in general). It's a way of putting old Stoic quotes and the Serenity Prayer into action.

Identify and understand the things you have total control over; do your best to manage them.

Identify and understand the things you have some control over; do your best to manage them, but don't stress the power you don't have.

Identify and understand the things you have no control over; do your best to "give no fucks" (as Mark Manson would say).

And the key here is in recognizing what you're trying to manage: outcomes vs. behaviors. As 2020 has shown us, you can not manage an outcome, but you can manage your behavior in the hopes of a desired outcome. What does this mean? Let's look at how you might be thinking about your goals:

Outcome example: I want to be headache-free by March 1, 2021. Or, I don't want to have headaches after March 1, 2021.

Awesome sounds great! But being "headache-free" and not wanting headaches are both outcomes; how are you going to make it happen?

Outcome goals and thoughts are "I want..." ideas.

Behavior goals and thoughts are "I will.." ideas.

Taken from Atomic Habits by James Clear. We’ll be coming back to that core of identity shortly.

Behavior example: I will exercise at my heart rate threshold daily. Or, I will perform my visual/vestibular training three times a day.

Behavior ideas and goals are tangible and actionable. You have full (or damn near it) control over these behaviors. Over time, these are the behaviors that will lead to your desired outcomes.

You can want something sincerely, but if you never take action - no one's coming to save you.

Control is nice. But are you ready, willing, or able?

We decide what we can control and what we cannot control. We choose what outcome we desire and what behaviors we can control and practice to achieve these outcomes.

The next step is deciding how realistic our behavior goals are. What works for you may not work for me, and vice versa…

So, how do we do this? We ask ourselves these three questions:

Am I ready to perform sub-symptom exercise daily?

Am I willing to perform sub-symptom exercise daily?

Am I able to perform sub-symptom exercise daily?

You may be 100% ready and willing to perform sub-symptom exercise every day, but you're not able to currently because you live in a tiny NY apartment, gyms are closed due to COVID, and your balance isn't safe enough to walk/jog/bike the icy roads. Harsh, but it is what it is. Adjust your expectations accordingly.

You may be 100% willing and able to perform visual/vestibular rehab, but you're not ready to make an appointment with a concussion specialist. Own that, and adjust accordingly.

We could go on forever. The point is that this type of honest self-reflection brings your behavior goals into focus. If one of these components is missing, you need to work with your concussion specialist to adjust the course.

Remember, even if the "perfect, miracle treatment pill" existed, you would still have to be ready, willing, and able to swallow it. No one is going to swallow it for you.

Loosen your grip. Your hands are going to cramp.

Now that we've established our sphere of control and our ready, willing, able status for our behaviors... Loosen the grip.

We tend to want things to be black and white, ones and zeros, good and bad, right and wrong, etc... But that's not life. "All-or-nothing thinking" only exists to drive you crazy. (And, that might actually be the only reason it exists.)

There's a spectrum, and it goes from better to worse. And this spectrum changes depending on your environment, resources, injury severity, etc...

Performing sub-symptom threshold exercise based on a BCTT or TERC murmur evaluation is better than strict rest.

Performing sub-symptom exercise without a test is better than strict rest.

Performing sub-symptom non-exercise activity is better than strict rest.

Performing sub-symptom exercise based on a BCTT is better than sub-symptom exercise without a test - which are both better options than strict rest.

The spectrum is not "good" to "bad." The range is "better option" to "worse option." And in any given situation of recovery, we can opt for the better option so long as it is a behavior/action within our sphere of control, and we are ready, willing, and able to accomplish the task.

What's better for a professional athlete may be a BCTT-driven exercise plan, while what's better for you may be tracking your daily step count and trying to add "100 symptom-free steps" each day. Neither is right or wrong; it's about finding what is going to work for you.

Getting unstuck. Finding clarity in your pursuit.

If outlining your sphere of control, deciding behaviors vs. outcomes, determining ready/willing/ableness, and putting it all on a spectrum is overwhelming and leaves you feeling "stuck," ask yourself these four questions:

What's good about not changing X?

What's bad about not changing X ?

What's good about changing X?

What's bad about changing X?

This is not a perfect system, but it's a great way to look at most sides of the coin when you're stuck in a decision rut. Below is a concussion-specific example of a question and some answers:

What's good about NOT performing sub-symptom exercise daily? I won't have to take time every day to exercise. I won't have to risk feeling crappy about my exercise capacity. I won't have to feel pressure to perform.

What’s bad about NOT performing sub-symptom exercise daily? I risk delaying my recovery further. I risk deconditioning and making my symptoms worse in a vicious cycle. I risk skipping the best-researched therapy for a concussion to date.

What's good about performing sub-symptom exercise daily? Research says this can begin to improve my sleep, mood, physical and cognitive symptoms in as little as ten days. In 5-6 weeks, neuroplasticity improves. My CO2 tolerance will improve. My autonomics will have a better balance, and my brain blood flow will improve. Etc, etc., etc...

What's bad about performing sub-symptom exercise daily? I have to complete it 6-7 days each week. I may experience an uncomfortable symptom flare if I work too hard. I may have to overcome and re-write some negative self-talk around my physical capacity or appearance.

The Responsibility/Fault Fallacy

The trend up to this point is two-fold: honesty and self-awareness.

What do I actually have control over? How can I let go of what I don't control?

What am I ready, willing, and able to do? What's good about that? Bad? Etc...

Recognizing, accepting, and owning your shit is the first step of hacking your mindset for recovery. But, why should you have to take responsibility for something you didn't even want or request? What if the concussion wasn't even your fault? Why should you be burdened with the responsibility of that?

I'll let Mark Manson take this one:

“Responsibility and fault often appear together in our culture. But they're not the same thing. If I hit you with my car, I'm both at fault and likely legally responsible to compensate you in some way. Even if hitting you with me car was an accident I am still responsible. This is the way fault works in our society: if you fuck up, you're on the hook for making it right. And it should be that way.

But there are also problems that we aren't at fault for, yet we are still responsible for them.

For example, if you woke up one day and there was a newborn baby on your doorstep, it would not be your fault that the baby had been put there, but the baby would now be your responsibility. You would have to choose what to do. And whatever you end up choosing (keeping it, getting rid of it, ignoring it, feeding it to a pitbull), there would be problems associated with your choice - and you would be responsible for those as well.

...We are responsible for experiences that aren't our fault all the time. This is part of life."

Fault is past tense. Responsibility is present tense. Your concussion/TBI is the baby on your doorstep; How orient to your injury and recovery is now your responsibility.

What do you control? What is completely out of your hands and a waste of your energy trying to control? What behaviors/actions are you ready, willing, and able to work on? Where can you loosen your grip and lighten your load? How can you orient to your injury and life in a way that serves you?

Change. Identity. Self-talk.

The last and arguably most crucial piece to behavior change towards a growth-mindset and recovery is re-writing the script about your identity.

We already covered a big mistake that you'll see many people making in their resolutions this year: focusing on outcomes (e.g., losing 20lbs) instead of focusing on tangible actions (e.g., walking 10min after each meal).

But we can only focus on actions and behaviors for so long if it does not fit the narrative we tell ourselves about ourselves. If our narrative and self-talk continually tell us that we're a "struggling, post-concussion spoonie for life" - then guess what? We are just that.

Here's a quote straight from, behavior change expert, James Clear:

"Imagine two people resisting a cigarette. When offered a smoke, the first person says, "No thanks. I'm trying to quit." It sounds like a reasonable response, but this person still believes they are a smoker who is trying something else. They are hoping their behavior will change while carrying around the same beliefs.

The second person declines by saying, "No thanks. I'm not a smoker." It's a small difference, but this statement signals a shift in identity. Smoking was a part of their former life, not their current one. They no longer identify as someone who smokes.

...The ultimate form of intrinsic motivation is when a habit becomes part of your identity. It's one thing to say I'm the type of person who wants this. It's something very different to say I'm the type of person who is this."

He goes on to say that it's not about reading a book; it's about becoming a reader. It’s not about running a marathon, it’s about becoming a runner. And so on.

Remember that creamy identity center? That needs to be the source of your motivation. (Source: Atomic Habits)

Bringing it back to concussion; it's certainly not about wanting to be headache-free by March 1, 2020. It's not even about being ready, willing, and able to perform sub-symptom exercise daily. It's a new narrative entirely:

I'm the type of person who likes to be physically active.

I'm the type of person who respects my physical, mental, and emotional boundaries.

I'm the type of person who eats to nourish my body.

I'm the type of person that/who... *fill in the growth-mindset blank*

Note from Dr. Mark: Some of you reading this may have found this from my Instagram. I see those of you who follow me, and I realize this may lose a chunk of you or offend some of you - or not. That said, I see your Instagram handles, hashtags, and social media "identities." I see the scripts and narratives bouncing through the echo chambers of social media, reinforcing "broken" identities.

If I haven't lost you at this point: I implore you to explore your narrative around your injury and your journey - are you @concussionstruggles123 or are you @alwaysgrowing123? Both handles could be from accounts that document a PPCS journey, but one portrays the identity of a head that's likely easier and more enjoyable to live inside. Your story is up to you.

Bringing it all together.

How was that for a blog-style crash course in behavior change psychology? Drawn from motivational interviewing and other behavior change research, you can see much of this comes back to an honest look in the mirror and owning the reflection.

If you want to make 2021 the year that you make the most progress on your concussion/PPCS, remember the following:

You write your script. "I'm the type of person that/who..."

Understand your sphere of control, and do your best to let go of the uncontrollable.

Others can offer help, but in the end, it's up to you. No one can swallow your pills, walk your walk, or perform your rehab but you.

You have to be ready, willing, and able to perform rehab. Or you have to be able to accept the outcomes associated with not performing rehab.

Whether it was your fault or not doesn't matter - your recovery today, tomorrow, and beyond is your responsibility. (Just like thar baby on your doorstep.)

Importantly, you are not alone.

There are TBI support groups, concussion specialists and specialty clinics, etc... that are all here to help you through this journey.

Dr. Mark Heisig is a licensed naturopathic doctor with continuing mTBI education from The American Academy of Neurology (AAN), Complete Concussion. Management (CCMI) and The Carrick Institute. His office is located in Scottsdale, AZ.